|

Terrahawks

SFX. Behind The Scenes Special - 1 ................. By David Sisson ................................. |

|

Terrahawks

SFX. Behind The Scenes Special - 1 ................. By David Sisson ................................. |

|

|

|

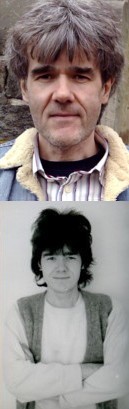

| John:

After leaving school, we went to Art College. I studied

Illustration and Steve did Industrial Design. During the

college holidays we filmed our own special effects on

16mm, at a small industrial film studio in Huddersfield.

To support the film work we compiled a visual effects

stills portfolio of models and designs, heavily

influenced by Century 21, and particularly the superb

work of Derek Meddings and Mike Trim. This period,

outside our formal education, became our apprenticeship

really, showing that we were serious about getting into

the film industry. In the meantime we’d tracked down

Alan Perry, who was a camera operator and director on

many of the Century 21 shows. David: How did you come across Alan Perry? John: Someone we met whilst hiring camera equipment to shoot our effects stuff said they knew of Alan’s TV commercial production company in Bradford. He was local to us and so we made contact. Alan was incredibly positive, kind and helpful, putting aside time from his busy schedule to look over our work and offer encouragement. His son was a film editor at Cosgrove Hall Productions in Manchester and he happened to know they were looking for modelmakers for a three-month contract on the original 'Wind in the Willows' film. Alan made the introductions and we went for an interview and got the job. We have a lot to thank Alan Perry for. |

| David:

So how did the job on Terrahawks come

about? John: Whilst at Cosgrove Hall, we heard that Gerry Anderson was crewing up to start a new puppet series at Bray Studios. We phoned Alan Perry and he phoned Gerry and made the introduction. I think it helped tremendously that we were already working in the industry. An interview was arranged and we went down to Bray Studios to meet Gerry and Bob Bell. At the interview, we showed all our work and had a guided tour of the studio. A few days later, the call came from Bob Bell telling us that we’d both got the work and could we start the following Monday? Fortunately for us, our contract only had a week to run so we were able to start almost immediately. David: I take it that you had watched the earlier Gerry Anderson shows? John: Yes. We grew up in the 1960’s, so we were very familiar with Century 21. There was simply nothing else that came close. |

|

|

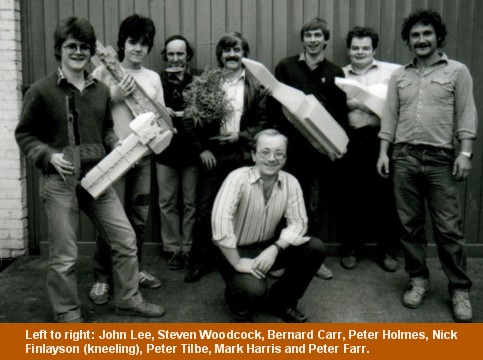

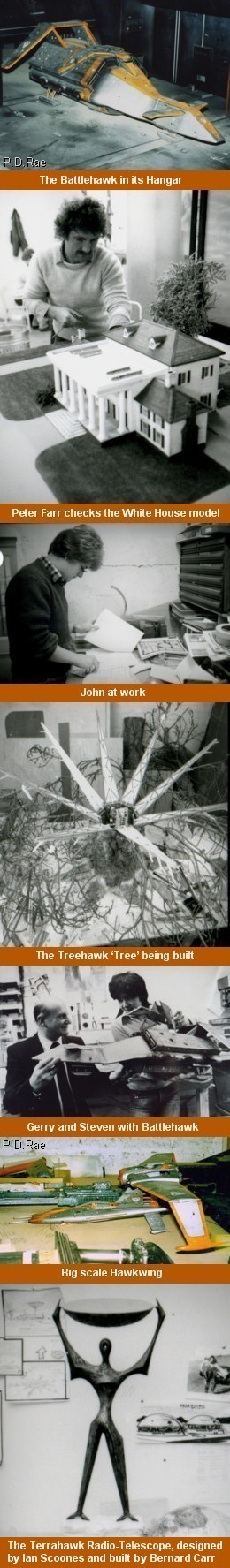

Steven:

I think John’s answer is somewhat understated. We

were completely obsessed by the Anderson shows as young

teenagers and knew them inside out. David: Do you have a favourite show or model design? John: 'Thunderbirds' was my personal favourite, it had a great blend of action, character and storytelling. My favourite sequences were the Fireflash/Elevator cars and the Crablogger vehicle. The series had a huge impact on me as a child. I can also still remember my first cinema experience, which was seeing 'Thunderbirds are Go' at my local ABC. I can vividly remember those Martian Rock-Snake creatures. In later years the first series of 'Space: 1999' was also a major influence to both Steve and myself, particularly as we were creating our own designs and models. Steven: Without doubt 'UFO' was the series that I enjoyed most when I was young. I also think that the first series of 'Space: 1999' is much better than was generally thought of at the time it first appeared. Really, it was ahead of its time as indeed 'UFO' was in the early 70s. I watched all of 'Space: 1999' on ITV4 not long ago and I thought the pilot episode, 'Breakaway', was extremely well done, watchable, and on a technical point superbly lit. As a 14 or 15-year-old when it first appeared I never did, and still don't, understand what people meant by the wooden acting of 'Space: 1999'. If anything, it was more like method acting, which is more like acting is today, where the melodrama is played down. The first series had something that very few TV series have ever had - genuine atmosphere. And no one can watch Barry Morse and call his acting wooden. The man is a joy to behold. David: Was Terrahawks your first science-fiction show and do you like to work in this genre? John: The answer is “yes” to both questions. Since then, I’ve worked in a number of different genres but I always feel at home with science-fiction. I have always wanted to develop projects for television and film, and was lucky enough to co-develop and produce a live action pre-school series for Carlton called 'Potamus Park'. It was moderately successful and ran for three series. Steven: I knew that I never wanted to stay working in special effects, even before I started working in special effects. I always wanted to write and direct live action and have made two cinema feature films in the past few years, 'Between Two Women' and 'The Jealous God', based on the novel by John Braine. They are both kitchen-sink dramas but the reason I made them is because it was easier to finance character driven period pieces in the UK than science-fiction. But science-fiction and action of the kind Gerry Anderson did well is where I’ve always wanted to be. Sadly, there isn’t the mindset in film and TV in this country for this kind of work. We seem to be more interested in making politically correct films and TV shows about “social issues” than entertaining people in the populist Lew Grade or Gerry Anderson sense. That’s what British TV has lost since the 1960s. It’s also why we have no film industry any more. David: Have you been involved in any other sci-fi projects? John: Yes. A year or so after Terrahawks, Steve, Mark Harris, Steven Begg, Nick Finlayson, and myself, went to work on 'Aliens' for Jim Cameron. More recently, I’ve worked on the miniatures on 'Casino Royale', 'V for Vendetta', 'The Hitchhikers Guide to the Galaxy', 'Alien vs Predator', and the 'Thunderbirds' movie. David: What model work did you do on that film, I thought 'Thunderbirds' was mostly CGI? John: It was, however there were two major model sequences. The first featured a highly detailed miniature of an oil platform; the other was a third scale monorail and tower, which collapses at the end of the movie. I also worked on models of TB:5, and the interior detail of the TB:1 swimming pool opening, both to augment the CGI team. I was also involved in set dressing on the underwater TB:4 set. David: What was the first Terrahawks model that you worked on? Steven: The White House. It was part made when we arrived and was basically a clear Perspex shell sitting on a blockboard base with a hole cut in it. We detailed and finished it. The hydraulic rams, which operated the folding walls, were made from brass by Nick Finlayson. The Perspex shell of the house itself was made by Bernard Carr, who also turned the Corinthian columns from acrylic rod. I still have a section of the White House launch silo, which extended like a shaft below the house model and was visible in the shot of the house when it was open and seen from above. John: When I look back, those first few months of pre-production were relentlessly hectic. There was a huge amount to make for the opening episode, which was in two parts. Steven: The second model we made was the Mars Base that was blown up at the beginning of episode one, including a separate large-scale close-up section. As with the White House, a few bits of the main model had been made as Perspex shapes when we took over. Mark Harris had made a wooden pattern and vac-formed the dormitory building at the edge of the set. We made the main section of the Mars Base in the centre to resemble a large mechanical hand, with the fingers splayed out, inspired by the feet of the snow Walkers from 'The Empire Strikes Back'. A wooden pattern had been made of one of the “fingers”. Under instruction from Ian Scoones, who was the original visual effects director, this was moulded in plaster and all the fingers were cast in wax so that when the model was blown up they shattered. We also used some Airfix railway footbridge pieces on this set, as a tribute to 'Thunderbirds'. David: Many early episodes of Terrahawks seemed to take place in the desert, possibly due to a lack of background buildings and scenery. Steven: We were never aware of this as a production policy, though it might for budgetary considerations have been something that was discussed between Gerry Anderson and Tony Barwick, who wrote most of the episodes. Obviously on the earlier shows they had a stockpile of models that could be used over and over again, a mountain from 'Thunderbirds' would appear in 'UFO' and buildings from 'Captain Scarlet' would be in 'Joe 90'. On Terrahawks we were starting from scratch and everything had to be built a new, so doing a desert scene was easier for us. David: Was anything brought in from other productions? Parts from an enlarged 'Space: 1999' Eagle section appeared in several episodes. John: Oh yes, it featured as a re-dressed close-up section of the Spacehawk. When we arrived at Bray, it was in storage and covered in layers of dust and polythene. I remember looking at it and thinking it was pretty good. Otherwise, I don’t recall any other items being used. |

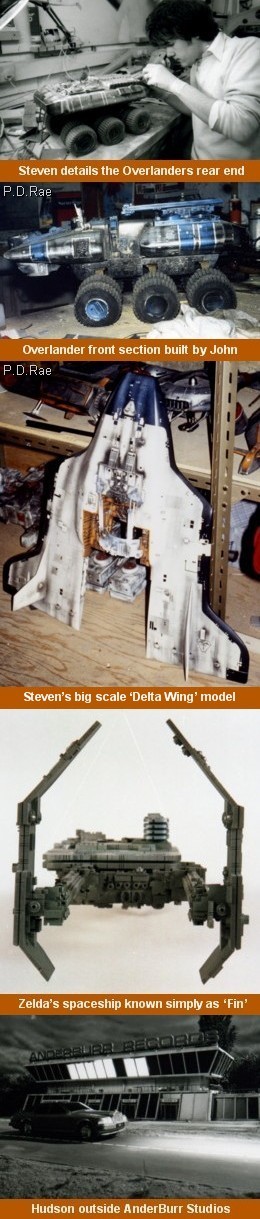

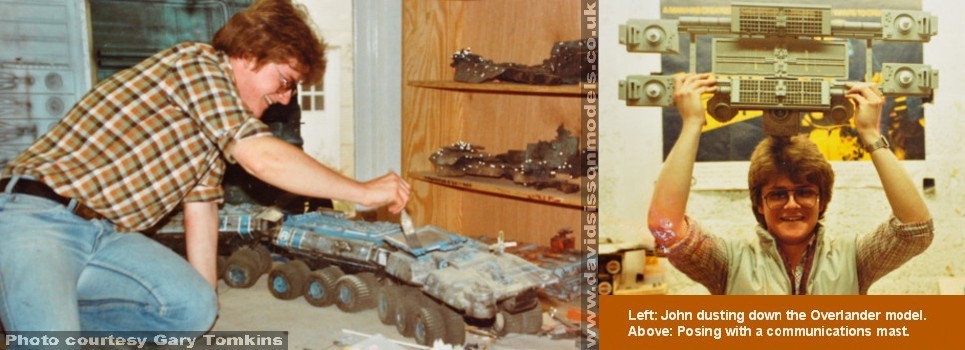

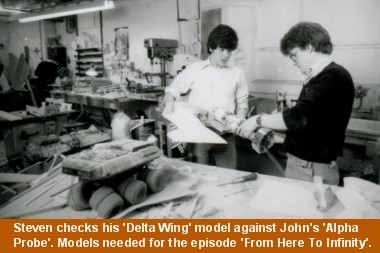

| David: How

long would a typical model take to construct and what

sort of materials did you use? Who decided the sizes and

how the models should be made? Steven: We usually discussed the potential size of the model with Steven Begg and Nick Finlayson. It was fairly obvious to us how large the models needed to be and how they should be made. We would often be limited by the size of the cyclorama or the short prep time before the model was needed. Sometimes, a component would dictate the size of the model. In the case of the Overlander it was the commercially available rubber tyres we used which dictated that it would be around five feet long. |

|

|

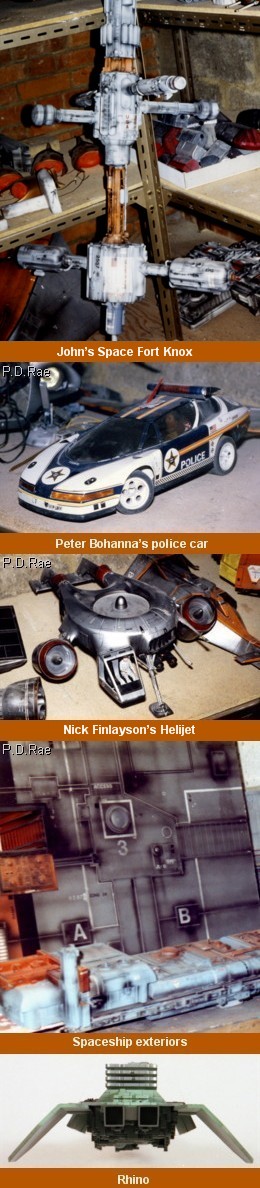

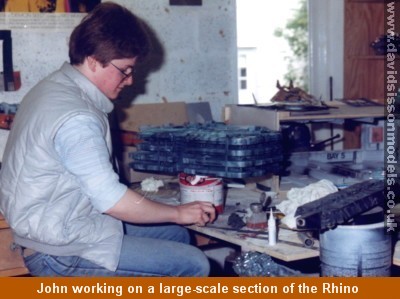

We spent about a

week or so making the major models, and sometimes only a

few days making the smaller ones. The materials we used

were jelutong wood, Perspex, Plasticard, and copious

amounts of kit bits and EMA. Also, we used to go along to

a plastic injection moulding company in Slough and fill a

van with reject components before they were melted down.

They made everything from hi-fi deck casings through to

bits of plastic used in washing machine manufacture.

These were a godsend and we used them to flesh out and

detail some of the models quickly, rather than having to

build everything from scratch. John: We made an episode about every ten days. The schedule was gruelling and the models often had to be made so quickly that we had to rely on instinct and use the first pieces that came to hand, which actually is a fantastically spontaneous way of working. We would read the scripts and go through any new models that were needed then just get on with it. We worked literally from scribbles on the backs of envelopes. David: What sort of input did you have into the design of each model? Steven: We completely designed most of the models that we built. Except for the main Terrahawks craft, we designed and made a great many used throughout the first series, from spacecraft through to oil refineries and lunar type bases. A couple of the models we made were based on designs by Steven Begg, such as the Overlander and the Delta Wing. He would provide a rough line drawing and we interpreted them freely while maintaining the essence of the overall shape. We never worked from blueprints but did everything by eye. John: We had a large input into the Zelda fleet. There was a basic star-shaped design concept drawn by Steven Begg very early on, which I feel we captured well; but we expanded on this with designs of our own. The paint finish of Zelda’s ships was also quite innovative. We started with matt black as a base colour and worked up through a lighter dusting of metallic greens and blues to give an alien feel. I also designed and built the ZEAF fighter. It was constructed around a hollow tube that slotted over a rotating rod on stage. This, in conjunction with the camera tracking towards or away from it, gave the impression of great speed. I made two versions, one around 12” long and a tiny one measuring around 2”. The filming techniques were quite simple by today’s standards but effective. CGI as we know it was still years away. Although the complete interlocked Zelda fleet, including the central hub, was quite large at six or seven feet across, the scale and relative size of each individual ship was very small at about two feet. We always wanted to make larger scale versions of them but due to time restraints this never happened except for once, where I made a big scale close up section of the Rhino, plus a close up flat featuring the Cubes being deployed through a hatch. This was shot vertically looking up, so that gravity allowed the Cubes to drop towards camera. These shots worked well, and were relatively quick to achieve. David: Which other models did you work on? Steven: Three of the main craft, the Battlehawk, the Terrahawk, and the Treehawk, were moulded in fibre-glass from wooden patterns and artworked by other members of the team, but they looked like shop display models. I remember John and me sitting in Gerry’s office and him despairing at the finish of the main craft, which had been detailed with panel lines that looked exactly like paving slabs. One of our first jobs was to strip them back down and repaint them and re-artwork them with realistic panel lines and Letraset, and weather them to make them look good enough for filming. My reference point for this kind of work was always Sky 1 from 'UFO', which I still think is one of the best two science-fiction hardware designs ever. (The other being the SHADO Mobile, also from 'UFO'.) John: Whilst we came up with the finished paint job on the main craft, and I assembled and artworked the Hawkwing, we didn’t actually make them. The patterns were made by Peter Tilbe. Often, when models such as these are constructed from blueprints, it is very easy for model makers to obsess about exact measurements rather than consider the overall sculpture. Model makers who are able to sculpt are generally good at design as well and therefore are in short supply. I recently had the pleasure of working alongside Mike Trim, and it was a joy to build directly from his concept designs. Working this way captures the essence of a design far better, and also allows you to sort out any slight ambiguities there might be, as you go along. Having Mike working alongside was great. |

|

| David: Did

all your designs end up on screen? Steven: All but two, as far as I can remember. I have an unused design for the Overlander, which I later adapted for a science-fiction TV series of my own that I was planning. I also have an unused design for the oriental-looking spaceship for the Space Samurai episode but it was subsequently designed and made by the late Pete Bohanna and was one of the few “main guest craft” that John and I didn’t produce. There were other models that we didn’t make, such as the dual helter-skelter shaped house set that Kate Kestrel lived in. I remember Nick Finlayson making a helijet and some kind of yellow contractor’s vehicle. I also remember Gus Ramsden making some wooden buildings for a street scene in the Sam Oaky episode, although I made Sam Oaky’s cabin, as well as the mailbox, the telegraph pole and all the junk in the yard. Pete Bohanna made a police car that was seen in the same episode. But John and I designed and made most of the featured craft, space bases, close-ups and other hardware seen in the first series. |

|

|

David: How

quickly did you have to work? John: Fast! What I learned more than anything else on Terrahawks was how crucial it is to stay on schedule. So it is inevitable that compromises have to be made along the way. The work must be as good as possible within the time frame. Steve and I made everything by eye and worked with a terrific energy and speed. Steven: We always made our models ourselves, from the construction right through to the finished detailing, artworking, and weathering. Occasionally, as happened with the Overlander, somebody else would make a bit of the functioning part of the model. For example John made the Overlander drive unit (the front section) and I made the two trailers. But Pete Bohanna made the undercarriage from metal. I always thought the commercially bought Tamiya rubber tyres that we used on the Overlander didn’t have detailed enough scale treads. But there wasn’t enough time to carve a master tyre pattern and cast 36 of them in rubber. David: Were you involved on the SFX stage, such as operating the models? Steven: Yes, sometimes we were. In the opening few episodes we were also involved in dressing the landscape sets on the SFX stage and painting a couple of the roller backings. One thing that sticks in my mind is a shot in 'Expect the Unexpected' where the Terrahawk lands on top of a cliff and puffs up a cloud of dust. We showed the effects guys how to achieve this using a can of airbrush propellant, a piece of thin tube, and a pile of fullers earth because we’d used the same technique in our own films. David: What interaction occurred between the model and puppet units, or were they completely separate? John: Both units were separate, with their own stages, and workshops. The puppet unit prop making was supervised by Peter Holmes, who was also ex Century 21. Steven: We sometimes liaised with the puppet unit. If you look at the Sram ship model used in episode three 'Thunder Roar', the cab section is very flat and angular, whereas the rest of the model has a traditional fussier SFX kit bit appearance. This is because the cab section had already been made by the puppet team when I started making the model. They were limited in what shapes they could achieve quickly on such a big scale and tended to work with flat blockboard, plywood, and Perspex sections because it was easier. So I had to make a wooden pattern to the same shape and design as the close-up cab section for the puppet, and vac-form it, so the two would tie in. But with the rest of the model I was free to design it how I wanted. This is typical of how we would interact with the puppet side of the show. John: Also, Des Saunders, who directed the episode 'Close Call', requested to see the Overlander model during construction. A puppet set had been made, so it needed to match. The cockpit on the model was underslung on the front drive unit, so they had to allow for this when shooting the puppet interior, with passing landscape visible beneath. From reading the script it was vague as to where the cockpit was, so this sort of discussion was crucial. There was also an instance when a large-scale section of spacecraft wing was made, and seeing as I’d made the model, I went over to the puppet workshop and panelled it to match. It might have been the Hawkwing but I’m not sure. David: Do you have any favourite model designs from the show? Steven: One model I always liked was the wooden shack for the Sam Oaky episode. It was nice to make something different to the usual sci-fi hardware. I also liked Sram’s ship and the World President 1, which was the last model I made for the series. John built the launch gantry for it. John: I liked the Zelda fleet, and the ZEAF fighter. I also made the Fort Knox space station and was particularly pleased with the results on screen. David: Did you feel that the models were filmed properly, to get the best out of them? Steven: Some of the models we made were shot from a closeness that was never intended, where the detail couldn’t hold up to such scrutiny. There are some shots of Zelda’s ships where the camera is so close that you can see the saw-cuts on the edges of the Perspex in front of the camera lens, even on 16mm. But I know why this happens and I’ve seen the same kind of awkward shots in all the earlier Anderson shows. A model is made and the effects director decides to improvise on the day and shots are done that don’t quite work. |

| What you have to

remember is how incredibly young we were and that this

was before the age of CGI. We were still working with

what were effectively tabletop toys. Everything was shot

in-camera. The people who had the biggest impact on the

overall look and style of the special effects in the

first series were probably Steven Begg and John and

myself. We were all only in our early twenties. Mark

Harris was the same age, and he had a big impact on the

puppet sets – plus he designed the Terrahawks

logo and insignia. Gary Tomkins, the Art Director, was

only 18 or 19 years old when we started – the same

age as my own son is now! David: What were your feelings on the finished program? John: I think many of the crew felt that it was never going to eclipse 'Thunderbirds', in terms of audience appeal. Steve and I were hoping it could be the start of another Century 21, but the reality of course was different. |

|

| Steven:

We knew from day one that it wasn’t going to work as

well as the original Anderson shows and that it could

have been better. Having said that, some of the younger

people I’ve employed on my own films remember Terrahawks

with great fondness, because they were kids when they saw

it and it was of its time. Looking back, I think that the expectation from Terrahawks was probably too high from the people who would be most critical of it. To me it wasn’t polished enough. The human puppets let it down badly, being obviously made from the same few basic moulds. Their tendency to gobble out their words and float around like Muppets meant they lacked the dignity on camera of the old marionettes and were too big. You never saw them in long shot like the original Century 21 puppets. This gave a claustrophobic feel to the series, which was something that the old shows never really had. I think the series would have held up better had it been shot on 35mm. It was made before the age of Super-16 and the old Standard 16mm looks very ropey by today’s standards. I think it diminishes how good some of the effects work really is. A digital clean-up would help it, and the colours could be pumped up in modern post. John: Thinking back I also missed the wonderful music of Barry Gray, whose contribution to the entire Century 21 back catalogue was immense and is perhaps largely under acknowledged. |

|

| David: Did

you stay with the Terrahawks production

until the end? John: No. We moved on after a year or so, to the TV commercials company Clearwater Films in London. It was there that we met and worked with Ken Turner and David Lane, plus other Century 21 people. Steven: I’d been engaged for two years before we worked on Terrahawks and couldn’t afford to get married on the wage I was on, especially as I was commuting home to the north every weekend to be with my fiancee. There came a point where the chance to earn considerably more working on TV commercials became irresistible. After a couple of years in London, I went back up north and set up my own advertising visual effects and modelmaking company. The work snowballed, and I ran this business for the next fifteen years, until I set up my film production company with my wife. |

|

David: What

do you think of today’s special effects? Steven: The whole CGI thing has revolutionised the industry but I think we are too dependent on it. Much of it, with its monotonous motion-control camerawork, leaves me cold. Fantasy films are looking increasingly like computer games, or rather the dividing line between the two is blurring. Some of the old Anderson shows feel laboured by today’s standards but, conversely, I find many modern action films and TV shows unwatchable because they induce a kind of mind-numbing vertigo due to the ridiculous camerawork and stroboscopic editing. As I said above, this is my personal view and it is probably a generational thing because I grew up getting used to seeing stuff shot in-camera, not put together in two dimensions on a computer screen and rendered. I’d like to produce an Anderson-type puppet series or earth-based live action show like 'UFO', but if I did I’d shoot it more classically, like the old shows, and subtly enhance the effects with only a small amount of CGI. My view is that good models and puppets are an alternative way of telling a story. It doesn’t matter if there are limitations and the puppets can’t walk, as long as your disbelief is sufficiently suspended. I’d take the deliberately retro approach and go back to basics. John: I can see why current movies are heading this way. During the last 25 years I’ve worked consistently in the industry and am well aware of the abundance of CGI. This is all part of a technical development that isn’t going to go away. It’s for this reason that I have always kept one eye on alternative areas of production and have continued to develop projects for the future. |

| David: Do

you still intend to pursue making your own Century 21

type TV shows? Steven: My sales agent, who used to be Lew Grade’s right-hand man from about 'Man in a Suitcase' onwards, keeps telling me that selling TV shows internationally is much tougher than selling films, unless you can fully finance via a major network, which is virtually impossible. There are more TV channels globally than ever before but it’s never been harder selling to TV. So I think that, in the world we live in, anybody looking to produce science-fiction of the kind that everybody reading this article would like to see produced has to think outside the box and might have to look at alternative ways of targeting that market – via the web for example. The Internet is going to massively change how we watch TV and I think traditional broadcasters are living on borrowed time. Similar seismic shifts have reshaped the reprographics and photographic industries and the cracks are already showing for ITV with falling advertising revenues. In the not-too-distant future, our TV sets will be hardwired into the Internet and we’ll download what we watch. That’s basically how my son watches TV already, on his laptop. As the process accelerates, producers will no longer need to sell to conventional broadcasters, most of whom will disappear. This change will democratize the world, with the Internet becoming a single gigantic TV channel, meaning anybody will be able to market their product via the web. David: I hear that you have plans to write a book about your work on Terrahawks. Can you provide any details on this? |

| John:

Well, even though Terrahawks seems to be

having a re-evaluation, it’s early days yet. When

Steve and I met a few months ago, we realised that Terrahawks

is 25 years old, which is quite nostalgic in itself. We

also have hundreds of behind-the-scenes photos of our

work and of the effects being shot; plus I came across an

old diary which states what was made, when and how. So

you never know. Steven: It would make for a pretty spectacular and very comprehensive special effects book about a Gerry Anderson series. Nowadays most of Gerry’s work is being meticulously catalogued and re-evaluated so if we think there will be sufficient take-up rate we can take it from there. The book will have to be of extremely high quality, otherwise we wouldn’t even consider doing it. But unless we could sell at least 1000 copies direct it wouldn’t be worth doing. The more people register an interest the better chance that the vast archive of SFX shots we have will see the light of day. David: Well I’d certainly buy it. John and Steven it’s been a pleasure talking to you, thank you very much for your time. |

|

.......... |

Many thanks to

Philip D Rae for the use of his colour behind-the-scenes

photographs.

Other photographs by

Anderson Burr Pictures Ltd.

'Terrahawks'

is copyright by Christopher Burr - No infringement

of copyright is intended - non-profit fan interest site only.

'Terrahawks' is a Gerry Anderson and Christopher

Burr Production.

David Sisson 2010

Back to INDEX ............................... Back to INTERVIEW SELECTION